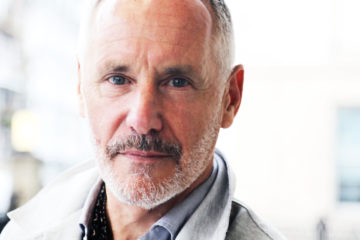

For the first time, Minnesota Opera is putting on Jake Heggie’s Dead Man Walking (2000), one of today’s most popular contemporary operas, and bass-baritone Seth Carico is leading the cast. I am thrilled that Seth was willing to take some time to answer my questions about the work, his career, and love of opera.

You will soon be playing the lead role of Joseph de Rocher in Minnesota Opera’s production of Dead Man Walking. This is an emotionally challenging role. Do you do anything before rehearsals or performances to get you into the right state of mind?

The most important step towards realistically playing a monster is finding a way to sympathize with him. You can’t really show how a character feels until you understand how he feels, and if you are still judging him at the same time, you will never really get to a realistic place. It often scares me when I find myself playing a particularly nasty character and I finally get to the point where I say, “You know, I think I see this guy’s point.” So, of course, I must find a way to sympathize with the character without emotionally transferring the darkness into my own life. For me the most important part of that process is meditation. A daily meditation practice is my key to finding the balance between going as far as I need to in a rehearsal or performance, but then when the work day is over, being able to recognize that the way I’m feeling isn’t real and putting all those emotions in a little mental box for storage, ready when I need them again but never getting in the way.

The short answer is yes. I do think there are a lot of stuffy little opera bullshit machines in the industry, but it’s not their fault. I was one myself.

Talk a bit about the vocal demands of the role. What’s the most challenging aspect of it vocally?

I’m sure everybody who has sung this role would give you a different answer to this question. The role has attracted a wide variety of voices, so the demands must also vary. Being a bass-baritone myself, this is definitely the highest role I have ever sung. I have sung roles with higher pitches in the past, but the tessitura here is just a whole new ballgame for me. There’s a lot of heavy singing in this piece, often in the middle voice, something I can imagine would be very tiring for a lyric baritone, but for me I feel right at home there. It’s singing sensitively for extended sections in my top voice that has created new challenges for me. But, I find nothing more thrilling than hearing a dramatic voice sing softly, and I want to try to live up to the great singers who have achieved that before me. I’ve never been one to shy away from a challenge, and I am loving the opportunity to learn new things about what I can do with vocal writing like this.

Has the opera changed the way you think of people like Joseph de Rocher?

Sister Helen Prejean spoke at my high school, and she single handedly convinced me that capital punishment was wrong, but that was quite some time ago. As far as my views on people like Joseph, in the few months’ time I have spent diving into this piece, I have given a lot of thought to who these guys are, and I have felt that I have a decent, privileged, well-off, liberal guy’s understanding of how they get to be the monsters we think they are. But what has surprised me since rehearsals began as I’ve actually been physicalizing Joseph, is that he is a child. We often talk about men like him as trapped animals, but I’m realizing it’s not a lack of humanity that is the problem here, rather it’s a lack of development. So, I’m trying to consider the way these men react and relate more from the perspective of desperate children, rather than caged tigers.

I see you’ve played George Benton in a production of Dead Man Walking. Is this your first time playing de Rocher?

This is my first time playing Joseph.

What adjectives would you use to describe your voice?

Colorful and metallic.

You have a long relationship with Deutsche Oper Berlin. Tell me about your time as a Young Artist there. Are there any differences between being a Young Artist in Europe and being one in the U.S.?

I was a Young Artist with the Deutsche Oper Berlin in 2010-2011. I have been with the company ever since in their ensemble. As far as the differences between Young Artist Programs in Europe versus the States, I can unfortunately only give you context from the one European program in which I participated. I’m sure others’ experiences have been different. American Young Artist Programs are much more about training the singers in a safe, nurturing environment, whereas Deutsche Oper’s program is time to sink or swim. It is made up of a crop of singers who are basically ready to sing anywhere, often a bit older than the crop at American programs. I had already begun my freelance career in America before I went to Berlin, for example. I don’t mean that to say they aren’t there to help you. They are, but they also expect you to be ready to do the work, singing at the top level, as their job is essentially finishing your grooming and putting you on one of the biggest stages in Europe. The pressure is high, and it is your chance to be introduced to a whole new market. They don’t want you to fail, so they are there to help, but there is no time for coddling.

I see you have a blog on your website. What prompted you to start that? Any chance you’ll get going on it again in 2018?

Years ago, I went through a major life change, discovering my personal journey into health and fitness. I wrote a lengthy note on social media about that journey, and several people encouraged me to write regularly. I wasn’t in the right headspace at the time, so I didn’t want to undertake that project until I had a proper vision and direction for what my writing would be. That health journey eventually took me to sobriety, and my experiences with that change are what gave me the direction for my blog. There are lots of things we are afraid to talk about in our business, and I saw that as my opportunity. If I could be honest with people, maybe it would help give them the courage to do the same. I will definitely be writing again. There is a lot to talk about these days, and my schedule has come back to a normal level lately, so I promise there will be more soon. I really didn’t want to commit myself to a writing schedule, as I only want to offer content when I feel like I have something important to say, since I am just a singer, so unfortunately that means the blog posts are few and far between.

I read your post entitled “Why Sobriety?” from May 4, 2016. I appreciate the fact that you’re so open about something quite personal. One line really caught my eye: “But, when does conformity take us away from who we really are as people and turn us into stuffy little opera bullshit machines?” Do you think there are a lot of “stuffy little opera bullshit machines” in the industry?

The short answer is yes. I do think there are a lot of stuffy little opera bullshit machines in the industry, but it’s not their fault. I was one myself. What I mean by that is that there is a whole mythology of glamor that comes along with our business. It is propagated all over the opera world. Opera singers are not all glamorous. We don’t all travel all the time shopping and eating fancy meals. Most importantly, we don’t all love being the center of attention, and we don’t all crave applause. Our tastes and passions are just as varied and unique as everyone else’s, but for some reason there is a push felt when one is a young singer to be the very model of an opera stereotype. We are told that we have to be a certain kind of person in order to live up to the industry’s expectations of us. Well, I tried. I hated it. I didn’t perform nearly as well since I was cutting off what made me special in order to fit the mold, and more importantly, I wasn’t an authentic person outside of performing. I set myself free from that thinking, and my work improved. The scary part is that the affect I have on other people can be polarizing. It can be difficult to accept that you might very rarely be the public’s favorite, since there is a large section of the opera audience that wants the stereotype to be true, but there are plenty of singers out there who authentically fit that image, so let them do it. You be yourself, and know that if some people don’t like you, that’s okay. If you climb into bed every night and know that you went through the day not pretending to be something you are not, believe me, you will sleep soundly. And you will discover that the tastes and passions of your audience are just as varied and unique as your own. So, if our public is made up of one-of-a-kind snowflakes, don’t we owe it to them to be the same?

What’s your earliest opera memory?

My earliest opera memory was Pagliacci in my hometown of Chattanooga, Tennessee, when I was in high school. I knew I liked singing, and I wanted to be an actor, but at that time, musical theater wasn’t really my thing. Having never seen an opera, I didn’t know that was a potential option. But that night everything changed. The baritone walked onstage in a pair of black slacks and a black shirt and sat down at a little table putting on his makeup while singing the prologue. He then put on a prosthetic hump and the rest of his costume. By the time he had finished delivering his lines, he had completely transformed into his character, the curtain flew open, and the show began. I was simply floored by what I witnessed, and I never looked back.

To finish, I’d like to ask a question I ask everyone: what is it about opera that touches your soul?

Opera is different for everyone. Some people like the spectacle and the artifice of it. I live for opera’s honesty. I love a giant expensive sensory extravaganza as much as the next guy, but there are special times when you might end up with a single person standing in a single spotlight, using the abilities of their voice and their personal emotional vulnerability to reach down inside of you and remind you that you are a living, breathing, feeling human being. That is what touches my soul, the simple fact that I know this art form exists and I can experience such raw humanity, both as an audience member and a performer. How lucky we are.