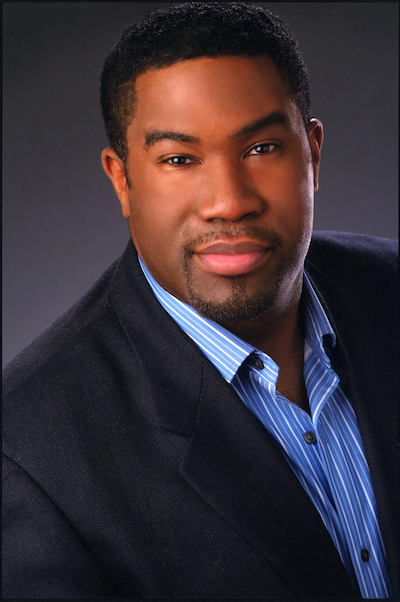

Bass-baritone Eric Owens is one of those guys whom everyone likes – and it’s so easy to understand why! He’s one of the most sought-after artists in the opera world, yet when you talk to him, it’s just like talking to a buddy of yours; he doesn’t take himself too seriously, nor does he have even a hint of an inflated ego: two traits that seem to plague those at the top of their games in the arts. I am absolutely thrilled that Eric was willing to sit down with me and answer a few of my questions about his Wotan in Lyric Opera of Chicago’s Ring Cycle, other roles he has played, and what it is about opera that touches his soul.

Eric Owens on Wotan in Lyric Opera of Chicago’s Die Walküre

I started off by asking Eric about the production I had just seen him in: Lyric Opera of Chicago’s Die Walküre. He plays Wotan in Lyric’s new Ring Cycle, which began last season with Das Rheingold. Lyric Opera of Chicago will be putting on Siegfried in its 2018/2019 season and Götterdämmerung in its 2019/2020 season. The full Ring Cycle will be presented at Lyric in three week-long cycles following the regular season in spring 2020. I didn’t have the opportunity to see Rheingold last year, so I started off by asking Eric how his Wotan in Die Walküre differs from the Wotan he played last season in Das Rheingold.

“This one’s got a lot more to say,” Eric said, laughing. “There’s a lot of text!” Indeed there is. Wotan has a crucial and challenging – both musically and emotionally – monologue near the beginning of Act II in which he explains his plight to his favorite Valkyrie daughter, Brünnhilde, played by Christine Goerke in Lyric Opera of Chicago’s Ring Cycle. Wotan is a stronger character in Die Walküre, according to Eric: “In Rheingold, it was the Löge show. Löge, once he arrived on the scene, he was the protagonist, more so than any other character, I think, especially when they go down to Nibelheim because Wotan doesn’t say much; he leaves that to Löge.”

Eric Owens as Wotan in Lyric Opera of Chicago’s Die Walküre

Photo credit: Cory Weaver

Speaking of that big monologue in Act II, I asked Eric what’s going through his mind when he’s on stage performing such a pivotal moment: is he trying to “become” the character? Is he thinking of the notes and technique? What about stage direction?

I’m trying to inhabit the character of Wotan as deeply as possible as he becomes the storyteller, the main storyteller that fills in a lot of blanks for Brünnhilde. As that’s happening, as much as possible, I’m trying to be in the moment of his situation and not in the moment of my situation.

“Not focusing on notes or technique, definitely,” Eric responded. “I’m trying to inhabit the character of Wotan as deeply as possible as he becomes the storyteller, the main storyteller that fills in a lot of blanks for Brünnhilde ([and] for people who didn’t see Rheingold). As that’s happening, as much as possible, I’m trying to be in the moment of his situation and not in the moment of my situation.”

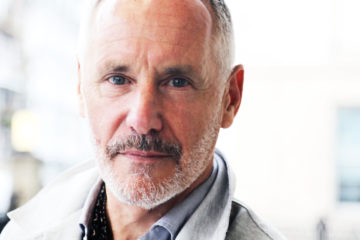

Eric Owens

Photo credit: Dario Acosta

And that’s exactly what Eric Owens does. His powerful voice is one that always makes you expect a big sound, but what you actually end up receiving as an audience member is an incredibly nuanced and contemplative sound, all as a result of the hard work he puts into diving into the psyche of every character he plays.

How do I know that’s what Eric does? He told me: “…and not until later, when he [Wotan] starts to talk about things that Brünnhilde already knows and some of the stuff she doesn’t know, that’s the moment when he starts to tell things to someone that he has never told anyone else. Their wills are joined, are conjoined, and she does end up doing what he deeply wants, but she gets punished because he knows that, as chief god, there are certain things that you might want to do in your heart, but your legitimacy comes crumbling down if you don’t do what is appropriate for your office versus what you want in your heart, and he knows he has to make that decision to let his son die. And at the end of that scene where he gets really, really cross with Brünnhilde in a way that I’m sure she’s never seen, there’s something going on that he’s not saying; I think he’s feeling, ‘do not make me lose two children in one day.’”

Wotan is not the only character Eric has played in Wagner’s tetralogy; in 2010, he played Alberich, a Nibelung dwarf who steals the Rhinegold from the Rhinemaidens, in the Met’s Ring Cycle. I had to know: which role is more fun?

“I don’t know yet. I’ve only, well, because I’ve only done two acts of this role [Wotan]. I’ve done all acts of Alberich, but I have yet to do the entire role of Wotan. So that’s a question I can’t answer yet,” said Eric. I pushed him. “Oh, well, as I’m aging, yeah sure, Wotan because he doesn’t have to run all over the stage. [laughs] You know, just from a practical standpoint he gets to be the king and he gets to just sort of sashay and saunter, whereas Alberich was just running all over the place and, you know, I’m 47 now and I’m just like, you know what? It’s good to be – in the words of Mel Brooks – ‘It’s good to be the king.’”

Eric Owens on roles composed for him

Throughout much of opera history, composers have known who was going to sing a given role on the opening night of a new opera. Consequently, many roles were written for specific singers. In today’s opera world, however, the majority of any major house’s productions are operas from the standard repertory. Consequently, very few of today’s singers are lucky enough to have roles created with them in mind. Eric Owens, however, is one of those lucky few.

One of the roles composed for him is the Storyteller in John Adams’ A Flowering Tree. I was curious as to how it feels to perform such a role, as compared to Wotans and Alberichs.

“Something that’s being written for you by quite a well-known composer of the day, isn’t something that everybody can say,” says Eric. “It’s an honor in so many ways to be a part of that process and to have the composer reach out and send you things and ask you, ‘Is this OK for you?’ When you think of the well-known composers of the past and you go back and you look at who was the first performer of Mozart, Puccini, Verdi [operas], you must think to yourself, ‘Oh my god. How must that have been?’ And did they really realize what that meant at that time, that centuries later that their names will be falling off the lips of people and singers just full of envy because they had Mozart write something for them.”

Any time you go to see a Ring Cycle or you go to see Tristan or Aida, you have people in the audience who have many, many singers via live performances or recording in their ear and there’s a comparison being made immediately. With a new piece, they can’t do that.

Beyond the excitement of having something composed specifically for you, Eric pointed out that there’s also the fact that singers in such a position do not have a performance history to compete with. “Any time you go to see a Ring Cycle or you go to see Tristan or Aida, you have people in the audience who have many, many singers via live performances or recording in their ear and there’s a comparison being made immediately. With a new piece, they can’t do that. So there’s a freedom to what you’re able to do and how you’re able to craft the character musically and theatrically, but with that freedom there’s an incredible amount of responsibility because you get to be the first at doing something. That’s a work of art or a piece of music that will most definitely outlive you, especially now when we have the ability to document it in a way that the first performances of any Mozart role could not be documented for future generations to hear and see what what the choices were that they made.”

Eric Owens on his love of opera

I’ve made a habit of asking everyone I interview what it is about opera that touches their souls. When I asked Eric, there was a very long pause. When he finally started to answer, his voice was different; it was quieter, more personal. This was a man who had clearly been profoundly affected by the art form.

Eric Owens

Photo credit: Paul Sirochman

“Well first and foremost it’s the beauty of the music and the power and passion of the human voice unaided by amplification to make a sound that fills a space and touches you in a way that very few things do, especially lately. To have that sound not only going to your ears but to hit your body. And it’s not just the voice; it’s the voice and the orchestra and in a discipline where so many other disciplines come to co-mingle and congregate and become one: singing, playing of music, ballet and dance, poetry via the libretto, the scenic arts with the costumes and the sets. Where else – in what other discipline does that occur?”

He wasn’t done quite yet. His passion kept pouring out.

“Especially when it’s just the naked, arguably first instrument of the universe: the voice – the human voice. The primal first, and to have it be developed to a point where so many people can hear you and be affected by it, and I’m talking about myself as a performer but also very much as an audience member, especially when it’s just really wonderful. There’s nothing like being a part of the audience and to have a performance make me forget that I’m a part of that profession, to make me forget and to keep me from reverse engineering all the things that I know are going on, that makes me that kid again who believes in the magic of theater and that’s something that’s always special. I’ve been lucky enough to have been to a few performances where my breath has been taken away. That’s always amazing.”

Indeed it is. Audience members the world over know that feeling well thanks to artists like Eric Owens.