Mark Adamo is one of today’s most exciting opera composers. His first major work, Little Women, was composed for Houston Grand Opera nearly 20 years ago. Since that time there have been over 100 productions of the work, and it is soon going to be on stage at Annapolis Opera. I am grateful that Mark was willing to answer a few of my questions about what it’s like to be a contemporary composer of opera.

I don’t get the opportunity to interview too many opera composers; most of the people I interview are interpreting the works of long dead men. As a composer, you are on the opposite side of things; singers and directors interpret that which is given to them by the composer and librettist, but you are the one actually providing the material to be interpreted. When you’re composing an opera, how do you decide how much direction to explicitly include in your work as opposed to allowing the performer the opportunity to discover it for her- or himself?

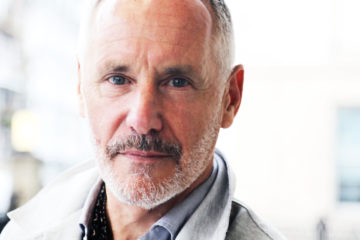

Mark Adamo

Photo credit: Jack Mitchell

You try to build as much interpretive information into the actual words and music as possible: not to make the opera “singer-proof,” (a term I deplore,) but to make of the opera as strong and shapely a loom as possible on which the artist can spin the fabric of the character. It’s worth remembering that, in theatrical terms, a score is, to the singer, a series of line readings. You are telling the performer not only what to say but how fast or slow, how high or low in her vocal register, when and how long to pause, when to sing quietly or strongly; the composer has a much greater degree of control over the vocalist’s interpretive choices than a playwright, by the script alone, has over an actor. This is terrific if the composer has thought through the rôle from the interpreter’s point of view, and fatal if he hasn’t; if the character herself hasn’t been expressively scored, there’s not a great deal the contralto can do to give the illusion that it has. On the other hand, you don’t want to make so many choices on the page that you’ve left only one minutely detailed, airlessly correct way to play the part. Then you’ve written, not a rôle, but a straitjacket.

You are telling the performer not only what to say but how fast or slow, how high or low in her vocal register, when and how long to pause, when to sing quietly or strongly; the composer has a much greater degree of control over the vocalist’s interpretive choices than a playwright, by the script alone, has over an actor.

Do you feel that there is a tendency in today’s composers to operate in a vacuum? What I mean is, do you think there is a tendency for contemporary composers to attempt to be completely original, as opposed to building off of or responding to the work that has already been produced?

There’s such a wide range of composers working now! But most of the ones I know work with history in a rather sophisticated way. David T. Little very much had Der Rosenkavalier in mind when writing an important trio in JFK; Thomas Adès has built in a bit of Bach and Ladino folklore into The Exterminating Angel. John Adams has leaned a great deal on Baroque models in his stage work, as Nico Muhly has on Tallis; John Corigliano‘s lone opera (to date) The Ghosts of Versailles is, among other things, an extraordinary minuet with Mozart. Even composers whose debts to operatic history are less obvious are still working with the past: Kaija Saariaho‘s L’amour de loin wouldn’t have been possible without the French modernism of the ’50 and earlier, and Missy Mazzoli‘s Breaking the Waves, I’d suggest, is in conversation with Bang on a Can post-minimalism, which is a way of thinking about music now at least forty years old.

…that’s when I began to wonder if I might make a home in, rather than merely visit, this musical world.

Tell us a bit about the first significant work you ever composed. What was it? When was it? How did you feel about the way it turned out?

Late Victorians: Late Victorians and other works, released on Naxos, USA, 2009.

That would have to be Late Victorians, which was the first piece in which I realized that perhaps I had something to say in the concert hall; up until that point I had thought of myself has a theatre songwriter acquiring compositional skills that I’d probably never get the opportunity to use. Late Victorians began as song cycle for a mezzo-soprano friend; but it was the year, of which there were many in those days, that the first people I knew fell to AIDS, and those losses became all I could think about. I tell the whole story of the piece here, but the short version is what started as that song cycle morphed, little by little into a symphonic cantata for singing voice, speaking voice, and chamber orchestra, with four instrumental cadenzas linking the movements; it was given an extraordinarily moving première by Eclipse Chamber Orchestra in 1995, and that’s when I began to wonder if I might make a home in, rather than merely visit, this musical world.

This season marks the 20th anniversary of your first great opera, Little Women. Congratulations! How have you changed as a composer in the last 20 years? Do you think Little Women would turn out the same way if you composed it now instead of 20 years ago?

Four sisters: Caroline Worra as Amy, Julianne Borg (seated) as Beth, Jennifer Rivera as Meg, and Jennifer Dudley as Jo in Little Women, New York City Opera, 2003. Photo credit: Carol Rosegg.

Thank you! One always likes to think one improves as time goes on, but I’m probably the last person to ask…What’s happened is that each new project—because it’s taken me into a different world of sound and drama—has taught me new skills. I don’t know if I’m a better composer now, but I’m probably a rangier one. And I’m actually planning to undertake a light revision—a polish, really—of Little Women, not to change the music per se but simply to make it bound off the page a bit more gracefully; there are some young-composer awkwardnesses in the rhythmic notation and the metrical plot, and I think I can make some of the string writing a bit more fluent (especially for the poor violas.) But I think I’d write the same opera today. It’s been an enormous friend to me over the years, and it’s still going strong: we’ve had over 100 productions since the premiere, and the newest, at Annapolis Opera, opens next week.

Let’s talk about Lysistrata, a work you composed based on the comedy by Aristophanes. How do you take such a light work with rather weak characters and transform it into something deeper that resonates with modern audiences?

Jennifer Rivera as Myrrhine and James Bobick as Kinesias in Lysistrata, New York City Opera, 2006. Photo credit: Carol Rosegg.

That was, indeed, the challenge! I go into great detail here: but the short version is that I ended up writing a new libretto based on the play I think we remember, not the play Aristophanes wrote, which is more of a political broadside with sex-farce interludes than a character piece. The biggest changes were the invention of Nico, the Athenian general with whom Lysia (the Lysistrata figure) is involved, who gave me an opportunity to talk about war in a more sophisticated way than Aristophanes cared to; and to make Lysia herself apolitical as the show begins, so she had more dramatic ground to cover. It was a reach: I kept only three scenes of the original, so it’s essentially a revision—a critique, even—of the source, so I was particularly grateful that so many listeners got what I was going for.

What are you composing currently? Typically how many different projects are you working on at any given time?

There’s a small chamber setting and a large-scale revision on deck at the moment: I tend to take on just one project at a time and concentrate on it exclusively. The singer Lisa Delan had the increasingly-popular idea of taking songs written by pop artists and asking composers like me to write entirely new settings: in this case, for her, the pianist Christopher O’Riley, and the ‘cellist Matt Haimovitz. (John Corigliano won a Grammy for a similar project a few years back, Mr. Tambourine Man: Seven Poems of Bob Dylan.) I’ll be scoring a lovely, spare lyric from 2004, entitled “About Today” by The National, a band you probably know. The revision is of my third opera, The Gospel of Mary Magdalene, which was given an extraordinarily well-performed première by San Francisco Opera and which nonetheless left me with the nagging suspicion that the show that we staged wasn’t exactly the show that I wrote. This summer I was given an opportunity to direct a revised version of the opera, in which the chorus was integrated into an entirely modern ensemble of 12 (for a total rôle count of 16—down from 73!,) and it was a revelation; with only small changes in look, tone, and tempo, the show lost nothing but gained enormously in agility, comedy, and style. So I’m revising the vocal score to omit the chorus permanently; and I’m mulling a chamber orchestration to match it, although the 16-member cast will take the full scoring very well.

Tell us about Becoming Santa Claus. Where did the idea come from? What is the work about?

It’s a funny story. When I was composer-in-residence at New York City Opera, I was sitting in on a rehearsal of our beautiful production of Hansel and Gretel, and found myself thinking, “Gee: parental abandonment, cannibalism, post-Wagnerian harmony—what makes this a Christmas opera again?” Which made me wonder: could I write a better one? That is, could I make a piece that—as The Nutcracker does for ballet—could introduce new listeners to what opera does, while at the same time making an opera that was not only produceable at Christmas, but somehow about Christmas in a way interesting enough that you could stage it outdoors in July on a 90-degree day and you’d still go?

Leaping Elves: Lucy Schaufer as Ib, Hila Plitmann as Yan, Jonathan Blalock as Prince Claus, Kevin Burdette as Ob, and Keith Jameson in Becoming Santa Claus, The Dallas Opera, 2015. Photo credit: Karen Almond.

The topic immediately suggested itself: the problem of gift-giving. As I write here, I struggled—as I think we all do—with the message of the season: if you love someone, max out your credit card! Obviously a problem: and yet there’s a delight, a glamour, in sharing all those shiny objects. Could I bring that topic onto the stage in a way that danced lightly but still dove deep? Then suddenly, a flash: “tween Santa Claus—Elf-Prince—as the original what-did-you-get-me Christmas brat?” (Which also gave me the idea of scoring all the Elf-royals in consistent coloratura vocal lines, which is the kind of composing I’d wanted to do for a while but hadn’t yet found the opportunity.) Then, later, just randomly, came the thought: “first instance of Christmas gift-giving: Magi, Matthew 2?” Which gave me the idea of making up a world in which both Santa Claus and the Three Kings held passports; of somehow coming up with a secular Nativity scene—the birth of the Santa Claus persona, rather than an actual person—and bouncing it off the sacred one.

All of which I liked, but none of which added up to anything until I met with Keith Cerny, the leader of The Dallas Opera, when I was there in town to rehearse Sasha Cooke, who created the title rôle in The Gospel of Mary Magdalene in San Francisco. He was intrigued, and commissioned the piece. That’s when I dug in further; and realized that the show, in its glamourous, fairytale way, could really be about people who ache to have, or be, perfect parents, and can’t; who use precious things both to show love when they feel it and to feign it when they don’t. Which is what it ended up being. It was, I must say, a delicious experience. The cast and production, as you can glimpse here, were nonpareil; the collaboration was virtually effortless; the company was happy; and the reviews were terrific. And the opera has just been released on DVD and Blu-Ray this season.

Your life in music is yours alone to create; another’s success doesn’t defeat you, another’s failure doesn’t validate you.

What advice do you have for students who are interested in becoming professional composers?

Write. You’ll never get to the good pieces if you don’t get the not-so-good ones out of your system. Write from love; write for friends; write for friends you love. Your life in music is yours alone to create; another’s success doesn’t defeat you, another’s failure doesn’t validate you. Always believe two things: 1.) that you have something, and 2.) there’s always more to learn.

To finish, I’d like to ask a question I ask everyone: what is it about opera that touches your soul?

It tells the truth, on time and in tune.