Michael Mayes is one of those performers whose portrayals stick with you. His tremendous successes in the world of American verismo opera, especially as Joseph de Rocher in Jake Heggie’s opera Dead Man Walking, are the result of a profound understanding and connection to the characters he plays on stage. I am grateful that Michael was willing to discuss his background and passion for the art form with me.

Tell us a bit about your childhood. I understand you grew up in Texas and didn’t have much exposure to classical music or opera.

I grew up in a rural community in the piney woods of East Texas, in a “town” called Cut and Shoot. I put ‘town’ in quotes because when I was a child, the ‘town’ consisted of a combination gas station/meat processing establishment, a town hall, and The Longhorn Saloon where many legends of the Texas Music Scene had regular gigs. Much has changed since then in the little community now that Houston’s urban sprawl has overtaken most of the undeveloped land between it and the nearby city of Conroe.

When I was kid, it was the kind of area where the second or third question upon meeting someone you didn’t know was, “Where do you go to church?” For me, it was New Bethlehem Baptist Church, a Missionary Baptist Church that had as its pastor a man of an extremely dubious nature from Kentucky who played the piano like Mickey Gilley and Jerry Lee Lewis’ lovechild, and preached with the same kind of fire and brimstone fervor that my Pawpaw, Pastor Virgil C. Mayes Sr. was known both in congregations around Houston and Dallas before his death in 1982. Growing up as the grandson of a BMAA preacher whose entire theology was steeped in the tent-revival era of The Great Depression definitely shaped the kind of artist I would become decades later.

What kind of music were you exposed to as a child?

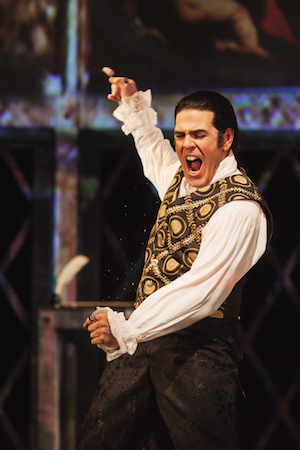

Michael Mayes as Scarpia

Sunday morning was when I got my theological education, first from my Mawmaw who was my first Sunday School teacher. We’d have Sunday School, then Big Church – break for the afternoon, then return at 6:00-6:30 for Sunday singing, and night church. Sunday night singing was where I got my earliest musicological education. Gathered around the piano with the music minister, and an assembly of choir members and musicians with guitars, banjo, mandolin, dobro and various other iconic instruments from the bluegrass tradition, we sang hymns notated in shape-notes from the Heavenly Highway Hymns Hymnal. I joined in these singing sessions early on, encouraged by my mother and father and mentored by Brother Green, who played along in all the church services with his grandson, Marvin, on bass- and who later invited me to join him on all Sunday services. This was a real gift to me, and Brother Green will always hold a special place in my heart.

Dad had the kind of job that allowed him lots of time to be close to home, as he patrolled the different pump stations that were his responsibility, often taking me with him and teaching me how to sing harmony along with George Jones, Hank Williams and Willie Nelson on KIKK, as we bumped along the broken asphalt, caliche and dirt roads that connected those far flung places. That’s where I learned to truly experience the act of singing for its own sake, purely for the joy of it. To this day, if you’re visiting Mom and Dad at their cabin in Creede, Colorado, you’re guaranteed to get an impromptu concert from my father, who will be out in the garage, working on some project, and playing George Jones CDs at 11 and singing just as loud, his hearing impairment making him blissfully unaware of the amplitude of his voice. It’s in those moments, that I smile, and thank him in my mind for instilling the same love of singing in me, not only in practice, but as a basic human value.

I didn’t really understand why anyone would pay hundreds of dollars to watch this [opera], and foolishly chalked it up to rich people liking to do things that preclude the possibility of sitting next to the great unwashed.

When did you develop an interest in opera? Tell us about your first experience with the art form.

My first experience seeing an opera was my freshman year in college; we were given a discount to see Samson and Delilah and in retrospect, it almost ended all of my operatic aspirations then and there. I remembered thinking, “All these people around me are in the throws of artistic ecstasy and I’m over here about to pass out, watching these people move slowly, sing slowly, act slowly, in a foreign language.”  I had the immediate impression that opera was just a bunch of people who like to sing loud, using a bunch of costumes and movement to give them an excuse to sing and get attention for 3.5 hours. I didn’t really understand why anyone would pay hundreds of dollars to watch this, and foolishly chalked it up to rich people liking to do things that preclude the possibility of sitting next to the great unwashed. It wasn’t until I finally got a chance to sing opera in my own language, about real people and the real drama that happens in their lives, that I understood the power of this art form to affect those who grew up without an appreciation of classical music, as well as those who did. Frank Maurrant in Street Scene was the role that hooked me early on. Feeling what it was like to actually tell a story in a theatrical way, with music that resonated with my own cultural experience, became the genesis for an entire ideology that wouldn’t truly come into focus until nearly 20 years later. A line could be drawn from that first experience with contemporary American verismo opera at a summer program my sophomore year at SFAU [Stephen F. Austin State University] in Nacogdoches, TX, to John Proctor in The Crucible in grad school, Margaret Garner after that, straight through to Dead Man Walking at Tulsa Opera in 2012 to where I am today, an artist that makes a living with a schedule, 80-90% of which is contemporary American verismo opera, or ‘Opera with a Conscience’ as I like to call it.

I had the immediate impression that opera was just a bunch of people who like to sing loud, using a bunch of costumes and movement to give them an excuse to sing and get attention for 3.5 hours. I didn’t really understand why anyone would pay hundreds of dollars to watch this, and foolishly chalked it up to rich people liking to do things that preclude the possibility of sitting next to the great unwashed. It wasn’t until I finally got a chance to sing opera in my own language, about real people and the real drama that happens in their lives, that I understood the power of this art form to affect those who grew up without an appreciation of classical music, as well as those who did. Frank Maurrant in Street Scene was the role that hooked me early on. Feeling what it was like to actually tell a story in a theatrical way, with music that resonated with my own cultural experience, became the genesis for an entire ideology that wouldn’t truly come into focus until nearly 20 years later. A line could be drawn from that first experience with contemporary American verismo opera at a summer program my sophomore year at SFAU [Stephen F. Austin State University] in Nacogdoches, TX, to John Proctor in The Crucible in grad school, Margaret Garner after that, straight through to Dead Man Walking at Tulsa Opera in 2012 to where I am today, an artist that makes a living with a schedule, 80-90% of which is contemporary American verismo opera, or ‘Opera with a Conscience’ as I like to call it.

For lots of people in our business, in order to understand Joseph de Rocher, they might have to do a ton of research just to get a glimpse into his psyche and cultural context. I grew up with Joseph de Rochers. Lots of them.

Michael Mayes as Joseph de Rocher in Opera Parallèle’s 2015 production of Dead Man Walking.

Photo credit: Steve DiBartolomeo

You have become one of the great interpreters of the role of Joseph De Rocher in Jake Heggie’s Dead Man Walking. I haven’t seen you perform, but I have seen pictures of you in performance, and I must say that even the pictures are quite powerful and haunting. You appear to so naturally embody this role of a convicted murderer on death row. How is it that you have been able to connect with the character so profoundly?

For lots of people in our business, in order to understand Joseph de Rocher, they might have to do a ton of research just to get a glimpse into his psyche and cultural context. I grew up with Joseph de Rochers. Lots of them. I was surrounded for most of my life at school, family reunions, football games, and church by men who could have been sent from central casting. My main barrier to entry for him was trying to find compassion for someone who represents an archetype that was so prevalent in the personae of many of those men I encountered in my upbringing. They seemed hellbent on punishing the world for one perceived slight or another, and lacking the requisite verbal skills to articulate that feeling, enacted that twisted form of entitled justice on any target with the requisite amount of vulnerability. I saw Joseph’s life played out over and over again in Cut and Shoot, so it was no leviathan task for me to gain insight into his psyche. It was his vulnerability that I had the hardest time cultivating in my mind, as someone who’d often been on the receiving end of some of his type’s most favored acts of victimization. The road to that particular understanding was indeed an arduous one, but I believe it is the most essential component of Joseph when trying to present a complete picture of this character. I find the most compelling performances with respect to playing “monsters” take one of two arcs: they either present as human, and are revealed to be a monster, or inversely, they present as monsters, and are revealed to be human, the latter of which is obviously applicable in Joseph’s case.

You will soon be playing Beck Weathers in Everest at Lyric Opera of Kansas City. Give us some insight into this production and your specific interpretation of the role in it. How does your understanding of mental health issues inform your interpretation of the role?

Michael Mayes as Joseph de Rocher in Dead Man Walking

In developing and eventually performing a character, once the historical framework has been established, I have to delve into the more nuanced areas of a character, and I often find, as with Joseph, that one’s life experiences, given that one has lived a life with varied experiences, are a great jumping off point. I’ve often said that the key to portraying a character with the most impact is to turn up to 11 those things which fall in the overlapping section of the Venn diagram between you and the subject of your exploration. With Beck, it was a relatively easy process.

Beck has been described as a driven, brash Texas conservative from Dallas who struggles with depression and suicidal ideation, only finding relief from the symptoms of that terrible disease through his mountaineering, putting his life at risk, and sacrificing the happiness of his family all to avoid the “black dog, depression.” His cure was almost as fatal as the disease, as he found himself left for dead by his climbing companions three times, teetering on the precipice between life and death at 28,000 feet above sea level. The basal elements of Beck’s story are very familiar to me. Beck had to travel to the top of the world to find his rock bottom. In so doing, he realized what he was missing in his life and how his disease and the desire to avoid its symptoms had almost cost him his life. Threatened with divorce if he went to Everest, he did so anyway, and upon his return, his face, hands, arms and feet all bearing the permanent scars of his enlightenment, was told by his wife “Peach” that she was in fact going to divorce him. He made a commitment to her to change, and his ‘probationary’ period of a year turned his life around 180 degrees. He rededicated his life to his family, and is still married to Peach and has worked since then to repair the damage that he had inflicted on those around him.

Beck had to go to Everest to find his rock bottom. I had to go to my rock bottom in order to find my Everest. The venn diagram, especially with respect to his mental health issues, is indeed one that has more in common than not. Mountaineering was Beck’s refuge, mine is the stage. His passion for climbing nearly ended his life, and caused those closest to him to suffer for years in pursuit of this passion. My passion for the stage is damn near analogical.

I remember watching an interview with Jason Alexander some time ago about his experiences after Seinfeld, and he said that he was sick of fans and entertainment professionals alike putting him into this “George” box, as though that were the only character he was capable of playing. Have you ever felt that becoming a fantastic interpreter of a role is limiting? Have you ever feared being put into a “De Rocher” box?

Michael Mayes as Rigoletto

[Laughs] Fortunately I don’t have that problem. While I am probably most known for JDR [Joseph De Rocher], the truth is that’s simply a product of the popularity and ubiquitous nature of the piece. What I hear most from people who’ve seen me in such disparate roles to JDR as Charlie from Three Decembers, or Manfred in Out of Darkness, Rigoletto, Col Thompson (Glory Denied), Scarpia, etc. is, “You’re like some sort of chameleon!” And I guess that is true to a certain extent; I enjoy wearing the masks, I think it’s healthy to take breaks and step out of one’s self once in awhile. The fortunate thing for people in this art form is that we get to do it on a fairly regular basis. I love to say that one of the beauties of our business is that we get to do things on stage that would get us arrested if we did them on the street. That’s truly an empathetic luxury unavailable to most people.

To finish, I’d like to ask a question I ask everyone: what is it about opera that touches your soul?

What touches my soul about opera is its ability to touch others, in ways only opera can. I had a woman drive from Kansas to Tulsa, OK who told me that DMW [Dead Man Walking] changed the way she thought about the man who murdered her daughter. I carry with me an AA sobriety coin, given to me by Laura Thompson, Col. Floyd James Thompson’s daughter, who told me that my performance gave her the chance she never had, to say farewell to her father from whom she was estranged at the time of his death. A man stood up after Glory Denied in Nashville and told us through a veil of tears, and later in more detail, of how this opera had changed the relationship between his son and his wife who had been deployed to Guantanamo Bay after the scandals that took place there. His son had begun to resent her for her absence and difficulty coping with the assignment. By his account, he treated her very badly for most of their relationship, making home life extremely tense, more so when she was home. His son, now a teenager, reached over and touched his dad’s knee after the final note, and told his Dad that he thinks he understands his mother more now. The father wrote to us later, to inform us that the relationship between his wife and his son had completely changed, and now the son not only treats his mother with respect, he also is genuinely affectionate, and more careful and loving with her. That is what touches my soul about opera: not that I’m touched, but that it can affect such real change in the lives of others, in such a beautiful way, and I’m allowed the privilege to be a part of it.