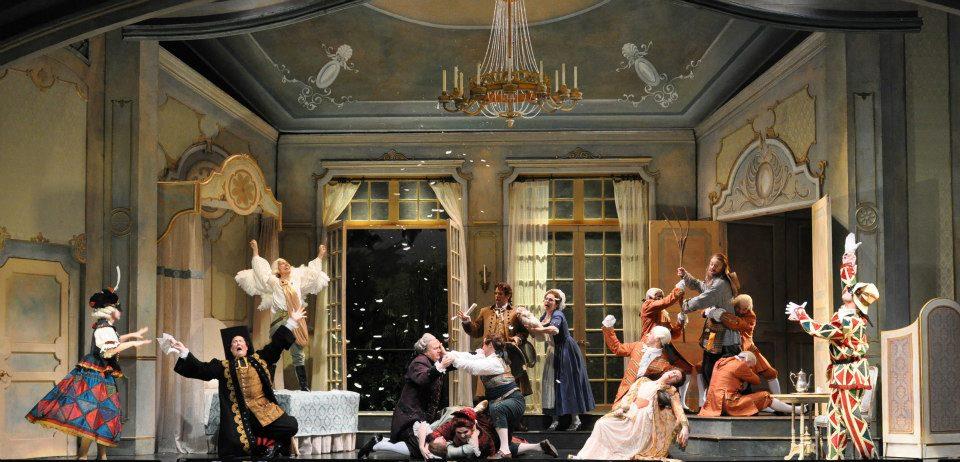

I’m with Wagner when he talks about how opera is (or should be) a gesamtkunstwerk – one of those terms that tends to pop up on college music history quizzes. I think of this term as describing an all-encompassing art form, a grand synthesis of media. Undoubtedly this describes opera, which brings together theater, music, stagecraft, costume, and story, just to name a few elements. What makes opera so fascinating is how it uses the interplay among these art forms to create something greater than the sum of its parts. Opera adds new, unspoken dimensions to stories, by way of something I call orchestral commentary.

One of my favorite layers of opera is what I call orchestral commentary. By this I mean that the orchestra itself acts as a character in the drama, commenting on, driving, emphasizing, or revealing something about the action. Let’s take a look at an example:

This is from Mozart’s Idomeneo. This is the first aria of the opera (Padre, germani, addio!), and it is sung by one of the lead characters, Ilia. She is a Trojan princess who was captured by the Greeks, led by King Idomeneo of Crete. The opera takes place right after the Trojan War. Ilia lost her father, brothers, and fellow Trojans in the war, only to become a POW. She has fallen for the Trojan Prince Idamante, Idomeneo’s son. Now that’s a tough break – falling for the dude whose father killed your family and besties.

The text:

Padre, germani, addio! (Father, brothers, farewell!)

Voi foste, io vi perdei. (You are gone, I have lost you.)

Gecia, cagion tu sei. (Greece, you are the cause.)

E un greco adorerò? (And must I love a Greek?)

D’ingrata al sangue mio (I know that I will bear the blame)

So che la colpa avrei; (of being faithless to my blood;)

Ma quel sembiante, oh Dei, (But Gods,)

Odiare ancor non so. (Odiare ancor non so.)

Listen to how the mood in the orchestra shifts at 0:29 – it moves from a dark g minor to a fleeting B-flat major as Ilia sings “Greece, you are the cause”. What does this change in feel suggest? Is the orchestra trying to tell us something? Perhaps it’s hinting that Ilia is navigating conflicting emotions: she’s distraught over the loss of her family but at the same time feels drawn to young Prince Idamante. Notice that she is not saying this with her words. Perhaps the orchestra is foreshadowing happiness that Ilia will feel later on in the opera. Perhaps the brevity of the major mode suggests that she may have short bursts of peace in her otherwise tortured life. I think you get the picture.

Jump to 1:02. We hear this part of the aria twice – once at 1:02 and again at 2:50. Compare those two passages. What do you notice? Ilia is singing the same text – “I know that I will bear the blame of being faithless to my blood” – but the orchestra again seems to be telling us something beyond the words. The first time we hear this passage, it’s in a major key, which makes it sound happy. The second time we hear it, it’s in a minor key, which makes it sound sad. Same text, different feel, again implying conflicting feelings. Mozart is trying to tell us something here, and the serious operagoer is anxious to pick up on it!

For those of you who have studied classical music, you’ll note that this repetition of sections in contrasting keys is not uncommon; sonata form employed in minor-mode works often closes the exposition in the relative major, and that’s exactly what’s happening here – this g minor aria moves to B-flat major before returning to and closing in g minor. That in and of itself is unexceptional, but what’s neat is how Mozart chose to employ this form for this aria and aligned the text in such a way that the combination of text and music reveals something more than either can alone. Talk about exciting!

This was just a brief exploration of a couple of spots of one aria of one early Mozart opera. Just think of how far down the rabbit hole you could go!